Pistachio Wars: The Back Story

Farmers are the key to power in California. They own the water. They own the land.

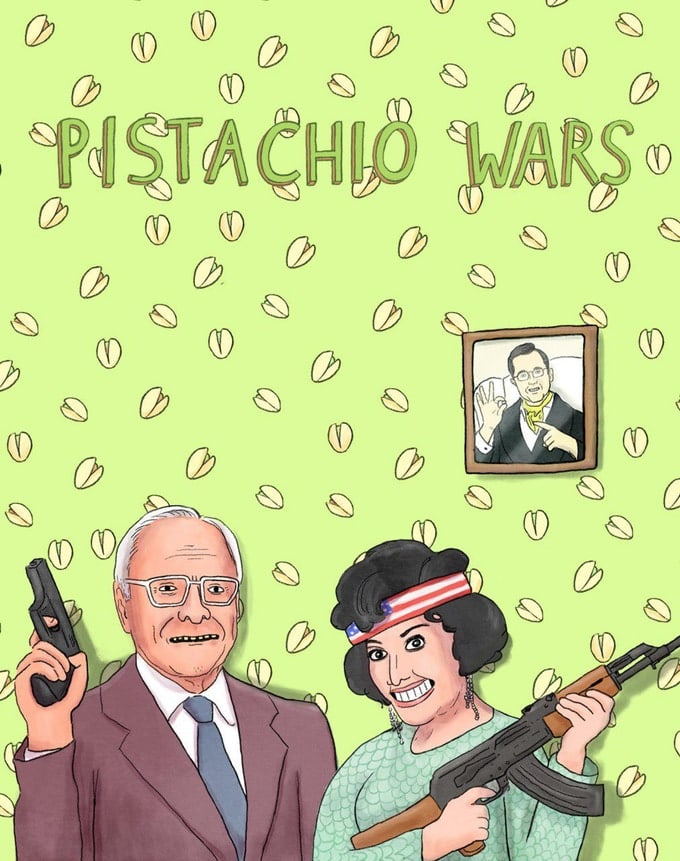

Last week, filmmaker Rowan Wernham and I launched a Kickstarter for Pistachio Wars, a documentary about the stealth privatization of California’s water — and the small group of billionaires who are driving it.

It focuses on a Beverly Hills billionaire power couple: Stewart and Lynda Resnick. They’re farmers — the biggest and most powerful in California. They’re also water barons. They control more water than the entire population of Los Angeles uses in one year — that’s 4 million people.

The doc tells a wild story. And it stands, in a very unexpected way, at the intersection of all sorts of ugly forces that are hitting us at the same time: oligarchy, global warming, environmental destruction, useless consumerism and marketing, the failure of liberal philanthropy, and America’s destructive neoconservative foreign policy. It seems like a lot of disparate issues to tie into a documentary about some pistachio farmers, but they all do come together in Pistachio Wars.

You can read more a detailed explanation of what the film is about here — and why we need your help to finish post-production. Check out the trailer!

What I want to do here is explain — and especially to readers who haven’t followed my reporting for very long — about how I got into this story, and how Rowan and I came to make this documentary.

It all started with a real estate crash

I first got on the trail of this billionaire water privatization story almost a decade ago, after I moved to Victorville, a subprime suburb in the middle of the Mojave Desert halfway between Los Angeles and Las Vegas.

That was back in 2009, not long after the housing bubble popped and the world’s financial system ground to a halt. I had just returned back home to California from Russia — after The eXile, the legendary English-language satirical newspaper in Moscow where I had worked, was shutdown by the Kremlin.

I had lived and worked as a reporter in Russia — which where I was born — all through the mid-2000s real estate bubble. I had watched from afar as the frantic scramble for ownership and speculation engulfed America. Entire new suburbs appeared on the fringes of California’s suburban sprawl almost overnight. It seemed to me that just about everyone I knew back in the states was buying and flipping houses and making a fortune in the process. Or at least that’s what it looked like. And then, of course, everything came tumbling down…

The global financial system went into a death spiral. Lehman Brothers, one America’s oldest investment banks, was wiped out. And the rest of financial system would have been wiped out right along with it, if it wasn’t the bipartisan bailout package hastily cobbled together and signed into law by a nervous and rattled President George W. Bush.

When I moved back to America, I wanted to understand what this boom was about — and to see what kind of civilization all this Wall Street speculation and greed created.

So I moved to Victorville.

Located on the edge of the inhospitable Mojave Desert, 100 miles east of Los Angeles, Victorville is perhaps the most barren, most remote exurb commuter town in Southern California. About an hour's drive from the nearest population center, the sprawling city is bounded by endless desert to the east, south and north, and a 4,000-foot mountain range that runs along its western edge. When I first drove over this mountain, I could only think of the Shield Wall of Arrakis, a natural barrier separating the desert and its horrors from the civilization.

Victorville was as pure a specimen of a bubble city as I could find — a city of cheaply constructed “master-planned” communities built to feed Wall Street’s insatiable demand for high-risk mortgage backed derivatives. It was city constructed on speculation and fraud at the highest levels of our society.

At the peak of the bubble in 2006, Victorville’s new McMansions went for half a million dollars a piece. Three years later, sellers were lucky to get a tenth of that. The city was devastated. Entire neighborhoods were evicted by banks and now stood empty — encircled by tumbleweeds and colonized black widows. They were so cheaply built that despite being only a few years old, many of the homes were already coming apart at the seams. It was an eerie place. It felt like a zombie virus had swept through town.

Initially, I planned on staying no more than six months, but became so absorbed by the place that I ended up staying for nearly two years. I reported on local real estate swindles, pissed off the city’s corrupt political elite, made the front page of the local newspaper, and got so deep into the petty details of Victorville politics that I seriously considered running for a spot on the city council. One thing I realized out there was that water was a key component of California’s real estate bubbles. Sure, Wall Street financing was important, but there could be no real estate speculation without some kind of shady water deals happening in the background. Most cities in California — whether San Francisco, Los Angeles or Victorville — were built in places without enough water.

This issue: water in California — who owns it, who controls it, where it comes from, and where it goes — became a bit of a journalistic obsession for me. One incident in particular set this obsession in motion.

When I was out in Victorville, California was in the grips of one of the state’s periodic droughts. The local water agency, which had to deal with the sudden doubling of the local population because of the real estate bubble, was in panic mode. It was running out of its groundwater supplies.

To keep people’s taps from running dry, it needed to get more water. And it did that by buying it — roughly $75 million worth — from a farmer hundreds of miles away. It was a one-time transfer of water that could sustain up to 30,000 families for an entire year, and it was shipped down to Victorville from a river close to 400 miles away via California’s government-funded aqueduct systems.

This deal intrigued me. Who was this farmer? How did they have so much water to spare during a drought? And why were they able to privatize and sell it? Water is an invaluable public resource, so it was strange to see a city buying it on the market from a private entity.

As I tracked down the details of the sale, it only got more interesting. The “farmer” selling the water was actually wealthy California family that owned cotton fields and almond orchards and controlled a real estate empire in the Bay Area, complete with office complexes, condominiums, mobile home parks, hotels and shopping centers. The patriarch of the family lived in a $11-million home in Los Altos Hills, one of the most expensive zip codes in America.

A multimillionaire family selling water to a poor out of the way city?

I read about this kind of privatization happening in Bolivia — where Bechtel strong armed the government into privatizing its water only so that it could buy it back from the giant corporation. But how was this happening in the supposedly progressive, tax-and-regulate California? In Bolivia, people rose up in revolt against the privatization of their water. But here it barely got mentioned as a minor news item carried in the local press. How was this not an outrage?

As I traced the water deal, I realized that it was just a drop in the ol’ proverbial bucket. Not only was California home to a private water market controlled by powerful farming families, but there was a plan in the works to stealthily privatize the last bits of untapped water in the state — all under the pretense of helping the environment and saving California from drought.

My interest in water began in Victorville, but it showed me a side of California that I had never realized existed.

People focus on Hollywood or Silicon Valley as the state’s most powerful industries. And indeed, they are powerful. But as I discovered, the true power brokers here are the farmers: They own the water. They own the land. And nothing happens in California without those two things — not even Silicon Valley or Hollywood can change that.

This small group of wealthy families run California like their own banana republic. They buy politicians, own towns, import migrant labor, pollute with impunity, and bend everything and everyone to their will. The story of California power is straight out of Roman Polanski’s Chinatown. The only difference is that it’s not fiction and it’s not ancient history. It’s happening today. Right now.

With Pistachio Wars, Rowan and I take a trip in their world. Check it out here!

Yasha Levine

December 3, 2018

New York